Because everyone loves a good story

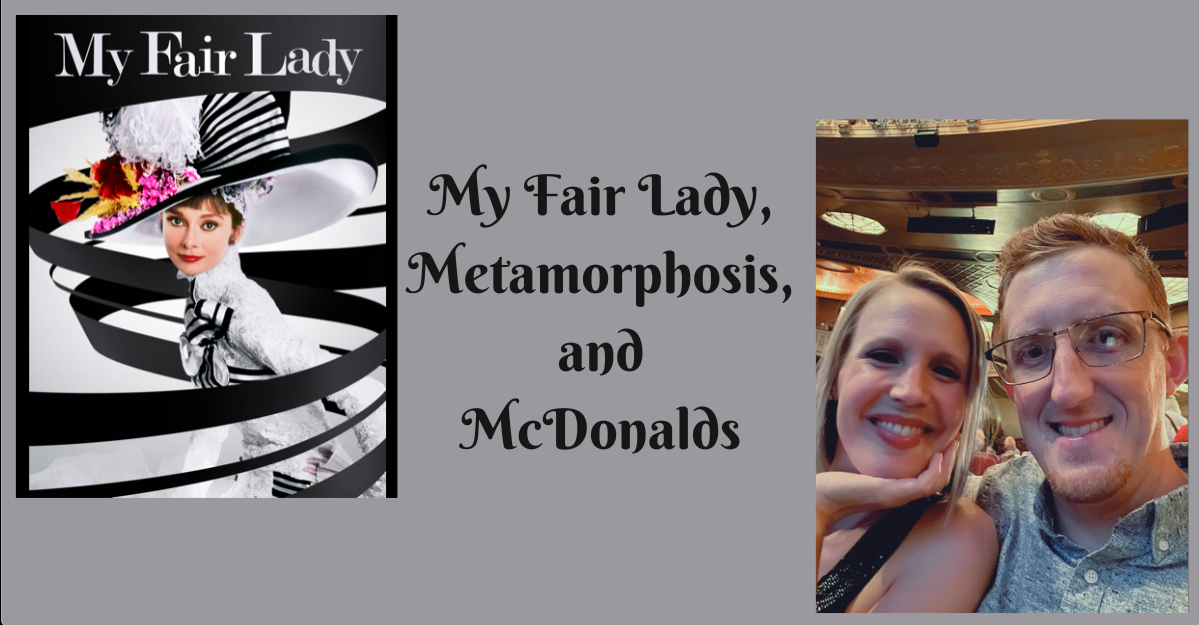

My Fair Lady, Metamorphosis, and McDonalds

Posted on August 19, 2022 by Emily Zaiser Wade

I don’t get out much, but when I do, it’s to see a Broadway play in Detroit.

For my birthday this year (as with most years) I couldn’t think of anything I needed or even wanted, so I asked for what I truly desired: a night out with my hubby seeing a play or a symphony or something. That’s my jam.

So we got two tickets to see My Fair Lady at the Fisher Theatre in downtown Detroit. My wonderful sister-in-law watched the kids at bedtime, I got (over)dressed in a black dress, and we enjoyed one of my favorite musicals from the vantage point of the fourth row. And afterward we hit up the McDonalds drive-thru so I could eat, like, a million chicken nuggets. I’m nothing if not classy.

The evening was a delight, and the play itself was as good as I’d hoped. Afterward I found myself contemplating one of the major themes of the play: transformation.

Pygmalion and My Fair Lady

Hopefully you’ve watched the old 1964 film of My Fair Lady starring Audrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison. Regardless, you’re probably familiar with the gist of the story because it shows up in various forms throughout literature and culture.

The first iteration of the story is a Greek myth. Pygmalion, a king and sculptor, carves a woman out of ivory and then falls in love with her. He prays to Aphrodite, and the goddess brings the statue to life. Pygmalion marries her and they live happily ever after. Centuries later in 1913, George Bernard Shaw wrote a play called Pygmalion. This play inspired a Broadway musical called My Fair Lady, which prompted a movie by the same name. I haven’t spent much time studying the myth, but I’ve fallen in love with every other version of the story.

The Particulars of the Plot

The play Pygmalion is not actually a retelling of the myth but a tale about transformation of another sort. Henry Higgins, a brilliant but heartless professor of phonetics, undertakes the challenge of recreating Eliza Doolittle, a coarse and uncouth London flower girl. She wants to rise above her low birth to become the kind of lady who sells flowers in a shop, not out of a basket in the street. To achieve this, she would need to overcome a lifetime of ghastly pronunciation and boorish mannerisms.

Professor Higgins boasts that he could do that and more—even pass her off as a princess within six months. His arrogance and obsession take over. He commits to her transformation, heedless of the cautions of Mrs. Pierce, his housekeeper, and Colonel Pickering, his friend and fellow linguist. The professor will do whatever it takes to recreate her.

The Characters

While the wit and humor of the script are well worth the read, it’s the characters that really make Pygmalion a classic. The play is well-named in light of the transformation that takes place not in Eliza Doolittle but in Professor Higgins. But the plot is also influenced by another one of my favorite plays—Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. Professor Higgins is ruthless in his training of poor Eliza, but when the metamorphosis is complete, she emerges as an entirely new creature—one he eventually finds hard to resist. Eliza, however, is not so easily won.

As I said, the characters are the best part of the story. Specifically, I enjoy the contrast between the main men. George Bernard Shaw captures four of the most diverse and yet relatable character types and showcases their effects on poor Eliza.

Alfred P. Doolittle

First, Eliza’s father, the ingratiating drunk. He’s never done a thing for her in his life, and yet he mooches off her continually. He guilts her into sharing her hard-earned money and then immediately spends it in the bar. He has no morals, no conscience, and no true guilt. Eliza tolerates him as family but can’t love him as a father.

Freddy Eynsfor-Hill

Next comes Freddy Eynsford-Hill, the rich, silly romantic. He falls in love with Eliza at the middle of her transformation—the point where her speech is flawless but her topics are far from acceptable in high society. He finds her enchanting and hilarious. Initially, Eliza is unmoved by his devotion, but she comes around in the end.

Colonel Pickering

The third man is Colonel Pickering, a true gentleman in every sense. While he agrees to help Higgins train Eliza, he never forgets that she’s a person with feelings and a future. He is her advocate and ally, treating her like a lady even before she looks or sounds like one. Eliza flourishes under his attention. She aspires to live up to his view of her.

Henry Higgins

The last and most important man is Professor Henry Higgins, the chauvinistic narcissist. From the first moment of the story, Higgins shows himself to care nothing for other people and everything for his research. To him, Eliza is merely an embodied challenge, a chance to prove his magnificent talent as a phonetic genius. He never stops to think of her as a human soul until it’s too late. In response to his overly-demanding treatment, Eliza stiffens and digs in her heels. She refuses to be bludgeoned into change. She flourishes in her own time and her own way.

What Causes Change?

The theme of transformation gives us a chance to ask the question, what causes people to change? Eliza didn’t change as a result of Higgins’ browbeating, blustering, or bullying. Instead, she responded to respect—the respectful way Colonel Pickering treated her, the acceptance as an equal from Freddy Eynsfor-Hill and even Higgins’ own mother, and the respect with which she comes to view herself. And that’s true of us all. We may modify our behavior to avoid mistreatment, but we change for the better under loving instruction.

That’s why the ending of The Taming of the Shrew doesn’t ring true to me. When I wrote a play as a retelling of that story, I was forced to change the ending. Threats don’t produce affection; compassion does. George Bernard Shaw recognized this, and it motivated his conclusion of the play.

The Metamorphosis Is Complete

In the end, Higgins proves that he can pass Eliza off as a princess. He couldn’t have been prouder…of himself. But Eliza’s true transformation isn’t a matter of mere phonetics but of perception. The moment she’s able to scorn his dismissive opinion of her is the moment she finally “comes alive,” as did Pygmalion’s statue. Her metamorphosis gives her the confidence to change more than her dialect; she changes her expectations which changes her future.

The play really is a work of art, right down to hilarious, insightful the stage directions. Please read it. And if you aren’t in the mood to put on your fancy clothes and sit through a Broadway production, at least promise me you’ll rent the movie My Fair Lady. I know you’ll love it. You could even do one better than I did and eat your chicken nuggets during the performance. Winner winner, chicken dinner.

Category: Family, FYI, Uncategorized Tags: Broadway, metamorphosis, My Fair Lady, Play, Pygmalion, transformation

2 Comments on “My Fair Lady, Metamorphosis, and McDonalds”

Want to leave a comment?Cancel reply

Subscribe to the blog!

Recent Posts

Add a comment, and join the conversation!

- Mark Wade on Two Poems for Good Friday and Easter

- Anonymous on Is Parenting a Waste?

- Anonymous on A New Podcast and a Plate of Pasta

- Coming of Age: Death in The Yearling – Past Watchful Dragons on The Yearling and the Hero’s Journey

- Coming of Age: Death in Peter Pan – Past Watchful Dragons on Coming of Age: First Love

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

Copyright © 2024 · All Rights Reserved · Past Watchful Dragons

Theme: Natural Lite by Organic Themes · RSS Feed

Wonderful review of Pygmalion and the film that spun out of it. Your background history of the story and the understanding of the different characters and how they influenced Eliza added insights I wasn’t aware of when I saw the film. I’m sure the stage play was especially exciting to experience. I would have to go with the classic popcorn over chicken nuggets though just to preserve that great theater experience. Entertaining and relevant.

I 💕 My Fair Lady! I also loved Taming of the Shrew. I can’t wait to have time to see a wonderful play again. I promise to rent My Fair Lady soon!